HOW MACHINES CAN LEARN FROM HUMAN BEHAVIOUR

Designing intelligent machines that can resemble and model human behaviour is closer than we think. And you can join in

Could a human behaviour simulator be embedded into a robot or online avatar to the point that it’s hard to distinguish between a real person or artificial intelligence? Scientists have been upping the stakes in this “Turing test” for years, to the point that human-mimicking programmes are ready to answer tricky questions, assist people with online shopping or be companions.

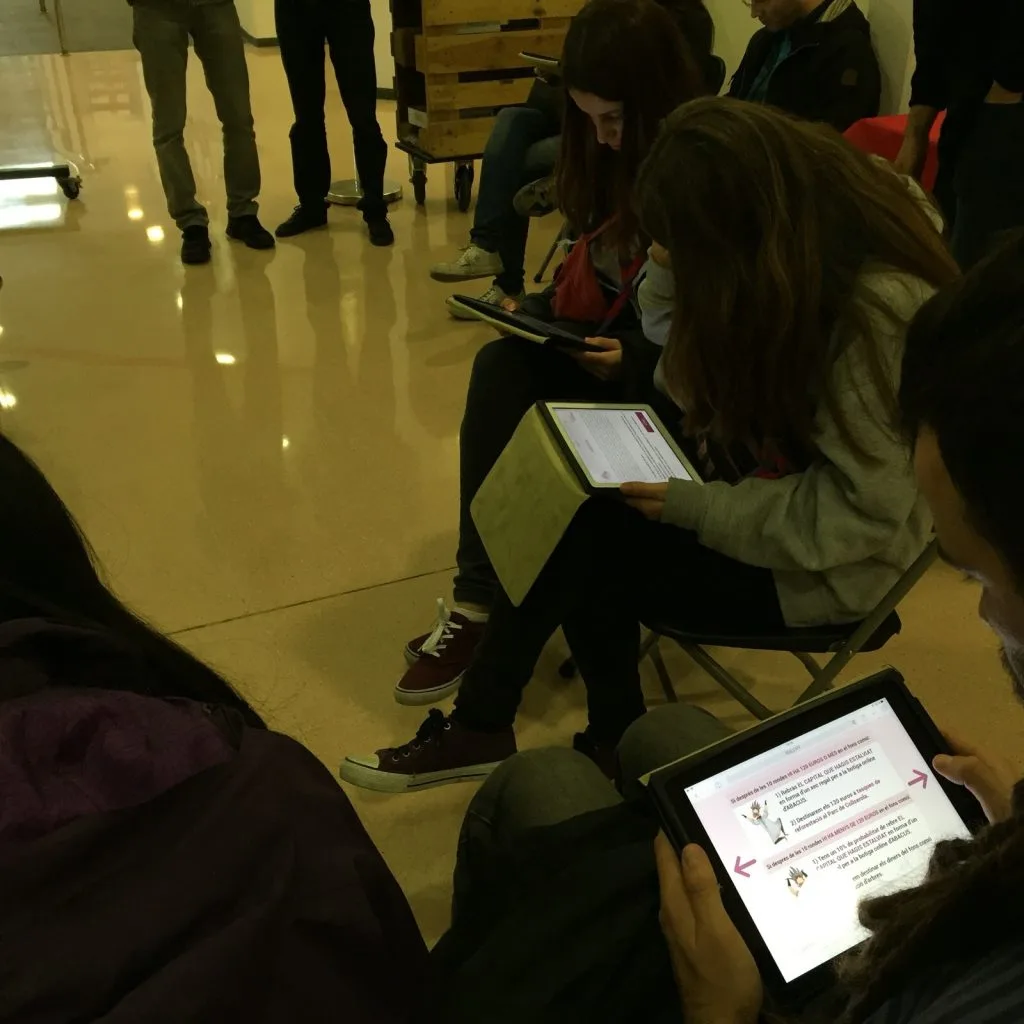

Now researchers across a clutch of European universities have developed a large-scale experimental lab programme involving over 22,000 people to investigate the socio-economic problems that arise from human-computer interactions. At the European IBSEN project, the researchers’ goal is to provide a breakthrough towards building a future human behaviour simulator, a technology that could impact fields from robotics to economics, and offer new instruments to policy makers.

According to project coordinator Anxo Sanchez, professor of Applied Mathematics at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain, the advance needed is the capability to do experiments with their actions. “Once you have an ample repertoire of behaviours, you could go for a simulator in which there are a number of computer agents that interact with each other with the rules you have, and therefore give rise to collective behaviour which should mimic that of society,” says Sanchez.

The researchers are looking at demonstration cases such as cooperation in social networks, where participants have to decide whether they want to collaborate with teammates toward some common goals, and how to foster and maintain that synergy when some are tempted to cheat and let the others do the work.

For example, in their experiments around 1000 people have been asked to decide how much money they wanted to give to a common pot, which will be equally shared among all participants, irrespective of their contribution. They then keep whatever they didn’t contribute, along with their part of the common pot.

The researchers realise that, after a few rounds, some contributors gave no money but benefited from the common pot, leading the others to reduce their sums and, eventually, not to donate anymore. However, in their large-scale experiments if people can’t possibly track down everyone else’s contributions, this makes the whole scenario different, Sanchez explains.

These experiments reveal that human behaviour depends on the way participants are informed of the outcome of previous rounds. “This is letting us model how people in a cooperative situation like this behave depending on the information received, and gives hints as to how more contributions to the common good can be promoted.”

Researchers are also looking to predict how people react when looking at online avatars in the business environment, such as online buying and selling. For example, Creative Virtual, a London-based company that offers virtual assistant avatars for customer service, already provides organisations with the capability to embed ‘personality’ and ‘emotions’ into online chatbots. “We see people interact with chatbots for longer when they are represented by an avatar that contains our small-talk module,” says Chris Ezekiel, founder and CEO of the company. “We even see people build ‘relationships’ with them, and this type of behaviour will only increase when they are combined with robots.”

One area where predictive power in human-computer interactions would be useful is in the service and healthcare industries. Cristina Andersson, consultant and coordinator for the national AiRo (Artificial Intelligence and Robotics) in welfare programme in Finland explains that “a hospitality robot needs to behave in a way that is accepted by humans whereas a manufacturing robot just does its job.” She says when incorporating behavioural rules into machines “there should be a piece of code somewhere saying that robots must obey the law. Then they will play the same game as we do.”

How to incorporate human behaviour into artificial intelligence (and how much) is one of the key questions in social sciences

These types of experiments can make online help and support services more human-like. A key question is what kind of human behaviour and how much of it should be incorporated into artificial intelligent machines and who will account responsible for their behaviour. “As long as the robots are not autonomous, the owner should be responsible,” says Andersson. “Or the user, if the user can change the robot’s behaviour.”

Like many other Future and Emerging Technologies (FET) projects, there is an element of risk and the researchers concede that the experimental design may not necessarily yield solid and stable answers to many questions. Social human behaviour is extremely fluid and, at times, irrational.

Readers interested in social human-computer interactions can register to participate in the ongoing IBSEN tests in exchange for an economic reward. The project is funded by the EU Horizon 2020 FET programme as part of a call for “novel ideas for radically new technologies”.

Cover image: via flickr.com.

Disclaimer: This story was originally developed as part of the FETFX project, the predecessor of our current initiative.