ENGINEERING HOPE: A NOVEL APPROACH TO SPINAL CORD REPAIR

What if damaged nerves could be guided to heal, rather than left to struggle on their own? What if materials could speak to cells using electrical signals, structure and chemistry? These reflections stayed with Paula Marques for years, quietly shaping the idea that would eventually become NeuroStimSpinal, a European project aimed at rethinking how spinal cord repair might one day be possible.

Those questions are rooted in a simple but harsh biological reality. The spinal cord is the body’s main communication highway, carrying electrical signals between the brain and the rest of the body. When it is damaged, those messages are interrupted or lost entirely. Because the central nervous system has very limited regenerative capacity, spinal cord injuries often result in permanent loss of movement and sensation. Unlike many other tissues, injured spinal cord neurons struggle to regrow due to inhibitory molecules, scar formation and a hostile local environment that prevents axon extension and reconnection (Nature Reviews Neurology, 2023).

Paula Marques is a principal investigator at the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Aveiro, in Portugal, and former NeuroStimSpinal project coordinator. For much of her career, she has worked with graphene-based nanomaterials, fascinated by their exceptional electrical properties and their potential use in health applications. Over time, her focus began to shift from what these materials could do in theory to what they might achieve in living systems. “I kept asking myself how we could make materials interact with cells in a more meaningful way,” she says.

The turning point came during a collaboration with Tecnalia, a research and technology centre in Spain. There, Paula encountered a decellularised extracellular matrix derived from adipose tissue, a naturally sourced material known for its biocompatibility. It contains several preserved proteins, specifically collagen, fibronectin, dermatopontin and laminins, a variety of proteoglycans including decorin, fibromodulin and prolargin and also some elastic fibers. “Within the neural tissue engineering framework, this matrix from the adipose tissue has never been exploited, to our knowledge”, she recalls.

“That’s when the idea clicked. I thought: what if we combine this matrix with the conductive properties of graphene to build a scaffold?”

That question became the foundation of NeuroStimSpinal. The project set out to develop an engineered neural scaffold that mimics the porous morphology of the native spinal cord while providing multiple signals to neural progenitor cells. By combining graphene oxide with the decellularised matrix, the scaffold could offer electrical, chemical, mechanical and topographic cues, guiding cells to differentiate into neuronal and glial cells. Beyond its therapeutic ambition, the scaffold was also conceived as a powerful tool for neuroscience research, helping scientists better understand how neural repair might be encouraged.

Such a bold and unconventional idea found a natural home in the Horizon Europe FETOPEN programme, now known as EIC Pathfinder. Unlike traditional funding schemes, FETOPEN allowed researchers to propose high-risk, high-gain concepts. “That freedom was essential,” Paula explains. “We were allowed to explore something truly new.”

Building the project, however, was not straightforward. Early funding attempts were unsuccessful, and the first FETOPEN proposal was rejected. “Those moments are difficult,” Paula admits. “You invest so much time and belief in an idea. But the feedback we received helped us improve and come back stronger.”

Gradually, a solid consortium came together. Seven partners from across Europe joined forces, including universities, research institutes and companies. Tecnalia played a central role in developing the biological component of the scaffold, while the Portuguese company Graphenest contributed its expertise in graphene materials. Other partners brought knowledge in biomaterials, neuromodulation and in vivo testing. “It was about finding people who believed in the idea and had the right skills,” Paula says.

Just as the project began, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted laboratories, travel and collaboration across Europe. Planned researcher exchanges were cancelled, and experimental work was delayed. Studies originally meant to be carried out at FORTH, in Greece, had to be rapidly transferred to the University of Aveiro.

“We had to adapt everything, protocols, training, timelines. It was exhausting, but we kept going.”

Further challenges followed. Ethical approval for animal studies in the Netherlands took much longer than expected due to strict national regulations. Coordinating a multidisciplinary and multinational team required constant communication and flexibility. “Managing the science was one challenge,” Paula reflects. “Managing people, expectations, and different working cultures was another.”

Despite these obstacles, NeuroStimSpinal achieved key milestones. The team successfully developed a biocompatible and conductive scaffold and demonstrated its performance in both in vitro and in vivo settings, including the implantation of a stimulation-enabled scaffold and battery device. Along the way, the consortium identified a major gap in the field: the lack of suitable systems to apply three-dimensional electrical stimulation in vitro. In response, they developed a novel stimulation device in collaboration with Graphenest. That device is now patented and undergoing further development.

Looking to the future, Paula remains both proud of what was achieved and aware of what could have gone further. She regrets that no industrial partner was ready to take the scaffold itself towards commercial development. “For future projects, I know how important that is,” she says. “You need that entrepreneurial drive from the very beginning.”

On a personal level, NeuroStimSpinal marked a defining moment in Paula’s career. Coordinating her first large European project strengthened her confidence and earned recognition from her peers. “It taught me that persistence really matters,” she says. “Innovative science often takes more than one attempt.”

Although the project has formally ended, the journey it began continues through new research initiatives and ongoing development. More importantly, Paula hopes that sharing this story will encourage others to pursue ambitious ideas. Research is challenging, uncertain and often slow, but it also brings deep satisfaction. As Paula puts it,

“When you truly believe in the science and in people you work with, you always find a way forward.”

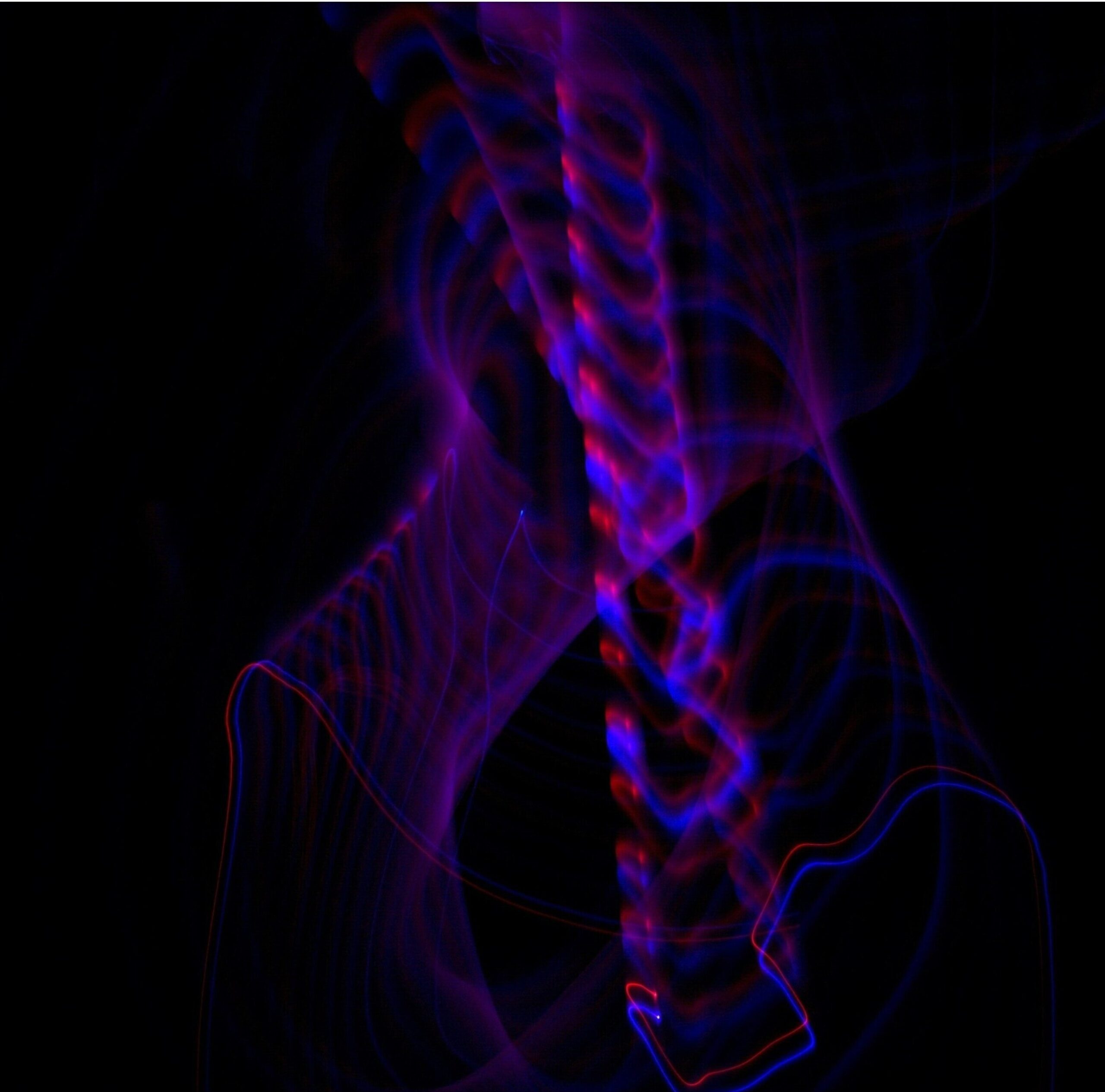

Photo by Tomás Mendes on Unsplash