A STORY OF TRANSFORMING BREAST CANCER CARE THROUGH PASSIONATE COLLABORATION AND INNOVATION

Breast cancer surgery has advanced significantly over the years, yet one crucial uncertainty remains: has every cancer cell truly been removed? For many women undergoing breast-conserving surgery, the answer only arrives days later, sometimes leading to further operations. The Spectra-BREAST project was created to change that reality. Behind it stands Carlo Morasso, a researcher determined to bridge the gap between laboratory science and the operating theatre.

When Carlo Morasso speaks about Spectra-BREAST, he speaks first as someone who works in a hospital, not as a technologist.

“I work every day side by side with medical doctors,” he explains. “You see the uncertainty and the stress patients face after surgery while waiting for the results from the pathologist. At that point, the need is no longer abstract.”

Carlo is Head of Laboratory at Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri (ICS Maugeri) IRCCS, a research hospital in Pavia, northern Italy. A pharmacist by training, he has dedicated the past fifteen years to translating analytical methods into clinical use. He is particularly passionate about optical spectroscopies, such as Raman spectroscopy, and their potential in biomedicine.

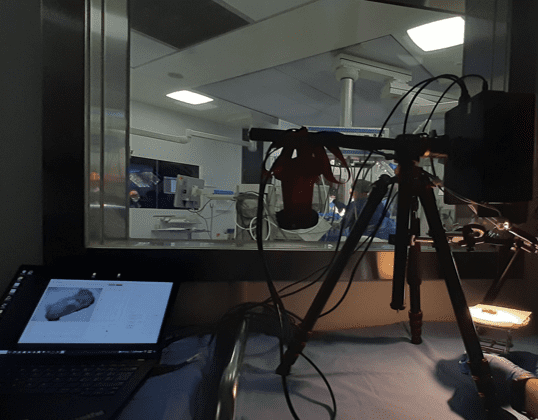

That long-standing interest found a concrete direction in Spectra-BREAST, an EIC Pathfinder project supported by the European Innovation Council. The aim is clear: to develop a device capable of providing surgeons with near real-time feedback on whether breast cancer has been completely removed during breast-conserving surgery, while minimising the removal of healthy tissue.

Each year, many women diagnosed with breast cancer undergo a lumpectomy. Although the tumour is removed during surgery, confirmation that the margins are clear relies on post-operative analysis. If cancer cells are detected at the edges, patients may need a second operation.

“Reducing reoperation rates would mean reducing a major source of stress for patients and improving their quality of life.”

The idea for the project did not emerge from a single event. “I remember the first time we discussed applying for an EIC Pathfinder project,” he recalls. “It happened independently with different partners, at a conference and at lunch.” He was also inspired by colleagues who had led EIC-funded projects and showed him that it was possible to push laboratory research towards real-world impact. In particular, Marina Cretich, who sadly passed away, played an important role in his decision to pursue this path.

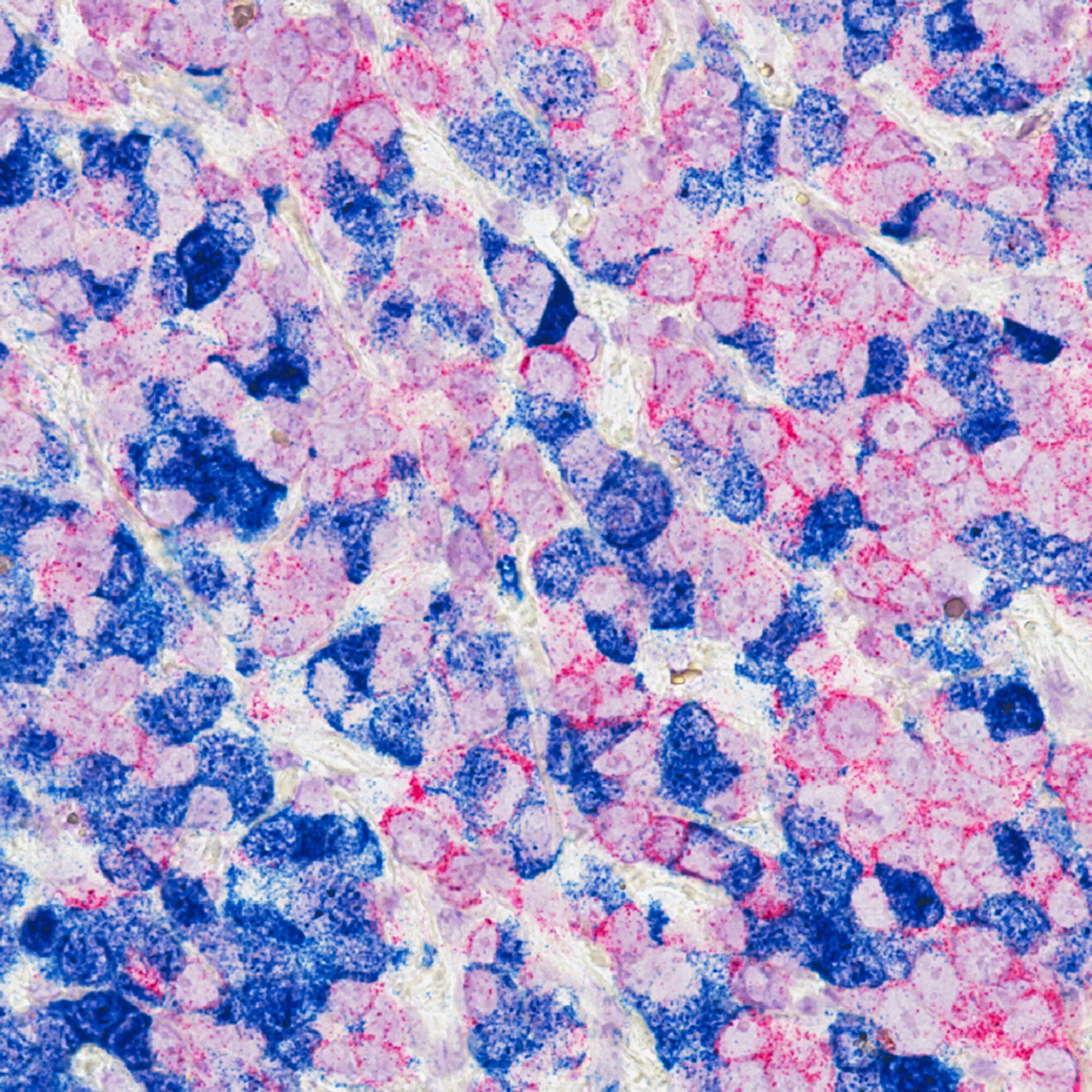

Optical spectroscopies have long been known to provide information about tissue composition. However, practical limitations have prevented their routine use in surgery. The turning point came when the partners realised that, by combining their complementary expertise, they could attempt to overcome barriers that had existed for nearly twenty years. The ambition of Spectra-BREAST is to integrate advanced optical imaging, spectroscopy, robotics and artificial intelligence into a single intraoperative device, so that each approach strengthens the others.

Building the consortium was, in Carlo’s words, “the easiest part”. The partners already knew one another and shared a common goal: to make science useful for people. The consortium brings together clinical, academic and industrial expertise. Some partners now run companies but have strong academic backgrounds. “The consortium was built not only on scientific excellence, but also on mutual trust and shared objectives,” he says.

Securing funding was more challenging. The EIC Pathfinder call is highly selective, and Spectra-BREAST was not successful on its first submission. “We worked almost two months on the proposal and were very close to the funding score, but it was not enough,” Carlo explains. Receiving the evaluation was difficult, but many of the observations proved pivotal in shaping a stronger resubmission. The team revised the proposal, looking at it through the eyes of external experts. “Believing in your idea is essential,” he says. “But looking at it from a different perspective made it stronger and more defined.”

Once funded, new challenges emerged. By definition, a Pathfinder project explores high-risk, high-gain ideas. Integrating multiple advanced technologies into a device suitable for use in the operating theatre is complex. Coordinating a multinational consortium adds further difficulty. Partners share a common goal but may also have individual interests. Key figures may leave, and the international situation has made supply chains more complex than when the proposal was first drafted.

“The most important thing for me was to keep each partner focused and to be open about problems,” Carlo explains. Open discussions often led to unexpected solutions and strengthened collaboration, sometimes even beyond what was originally planned.

Maintaining motivation requires perspective. “In science, everything seems to move slowly,” he says, particularly in medical research, where regulation is rightly strict. When progress appears limited, he looks at the work already achieved. “Often, what seems blocked is actually a series of incremental but continuous steps.”

He also values being part of a wider research community. Recently, when facing a data management challenge, the team discovered that a contact had launched a project on a similar topic. A simple exchange of emails opened the door to discussion and possible solutions.

“Scientific progress is not a single-person effort, collaboration is key.”

Twelve months into the project, it is too early to measure long-term impact. However, promising preliminary results suggest that the development of a usable device for advanced optical analysis in the surgical room is realistic. Over the next three years, the team will test the system in more realistic scenarios, assessing not only technical performance but also usability and integration into clinical workflows.

In the long term, Carlo imagines tools like Spectra-BREAST becoming part of everyday surgical practice, much as endoscopy and robotic surgery are today. He envisions surgeons being able to “see” disease features that are currently hidden, improving precision and reducing the impact of surgery on patients’ quality of life.

On a personal level, coordinating the project has been both demanding and transformative. Coming from a technical background, managing administrative, legal and partnership aspects at this scale has sometimes felt overwhelming. He credits his wife and his three children for helping him maintain balance.

Carlo reflects:

“At the same time, being the coordinator of an EIC Pathfinder project at this moment in history is a real privilege. Today, AI and robotics are becoming pervasive in both research and society. Working at the intersection of this transformation and clinical practice feels like being at the centre of a structural shift. Spectra-BREAST forced me to think bigger. I have learned much more about leadership, collaboration and impact than I expected.”

Photos: Spectra-BREAST project

Cover by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash