CAPTURING AND CONVERTING CARBON DIOXIDE IN ONE BREAKTHROUGH DEVICE

Single system that both captures and transforms CO₂ into useful fuels is an environmental and energy challenge win-win. A European innovation in ‘double active’ membranes could redefine how waste carbon emissions can be turned into energy.

Big things have small beginnings. In a lab at Italy’s Institute on Membrane Technology, Senior Researcher Alessio Fuoco contemplates what, at first glance, looks just like a modest piece of industrial glassware- currently closer to a thin plastic film than a finished device, as the full system is still under construction -about the size of a tablet computer. But it’s what’s inside the box that matters. Within this early prototype lies a molecular concept in catalytic membranes that could help reset our relationship with carbon.

“Basically, we want a single device that captures and converts CO₂ at the same time.”

Says Alessio from the ITM, part of the National Research Council of Italy (CNR), the coordinating institution of DAM4CO₂ (Double Active Membranes for a Sustainable CO₂ Cycle), an European research effort investigating ways to convert carbon dioxide emitted by industry into renewable fuels.

DAM4CO₂ aims to close the carbon loop not with vast carbon-capture installations that promise much and have yet to deliver, but by demonstrating a compact, integrated approach. While the current prototype is small, the envisioned device will likely be larger than a desktop unit – yet still far more compact than today’s industrial machines. Designed to be something modular for different industrial sites, its initial scalable form would be comparable in size to a standard shipping container. If successful and brought to scale, the same system that captures CO₂ could also convert it into synthetic fuels, eliminating the need for separate capture and conversion plants.

Double active, double benefit

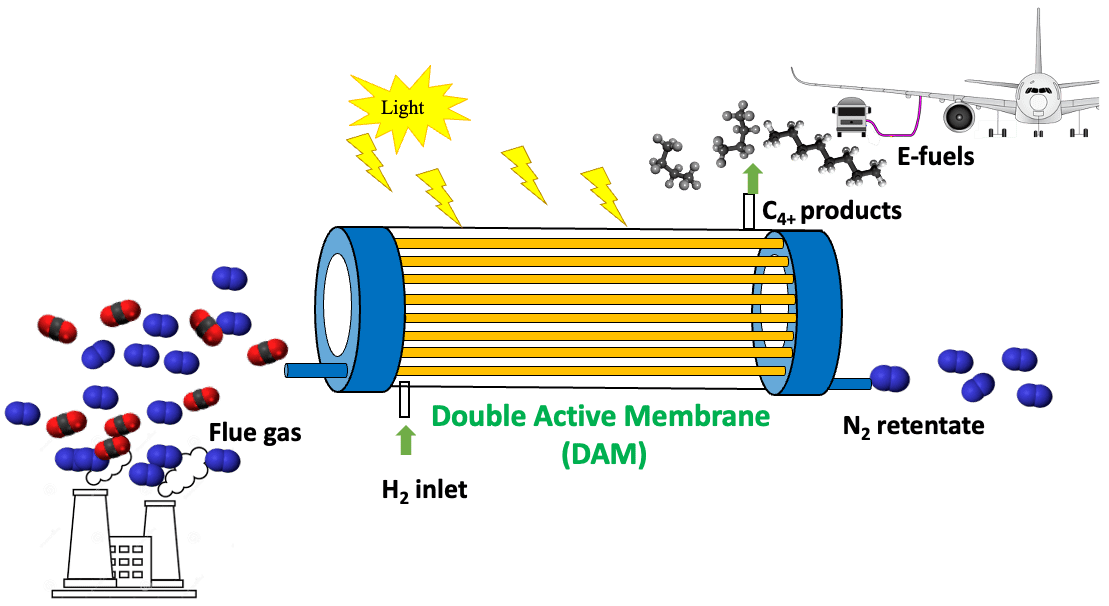

The project aims to integrate two technologies that typically operate independently: membrane separation and photocatalysis. At the heart of the concept are membranes, delicate films that act as molecular sieves. Membrane-based technologies could play a key part of the process. Thanks to their high efficiency, scalability, and easy operability, they are candidates for the efficient capture and use of CO₂.

“You can think of membranes as filters on a molecular scale,” Alessio explains. “They distinguish one molecule from another.” In DAM4CO₂, CO₂ molecules are guided through these membranes, while other gases are blocked. Beyond the membrane sits a light-activated photocatalyst that converts the captured CO₂ into valuable chemicals – specifically C4+ molecules – which can serve as building blocks for synthetic fuels.

So far, so simple. Traditional large-scale chemical membrane modules are made of steel sturdy enough to withstand industrial wear. But light cannot pass through steel, so DAM4CO₂’s engineers had to build theirs from quartz and glass instead, carefully balancing transparency, durability and chemical resistance, developing double-active membranes with a durable and highly selective gas separation layer and a photocatalytic layer.

“We’re making the membranes from scratch. They’re not yet perfect, but the first results are encouraging.”

Says Alessio, adding that this is early Technology Readiness Level 1-4 technology, funded by the European Innovation Community (EIC) Pathfinder grant. This type of funding specialises in supporting the earliest stages of scientific, technological or deep-tech research with high risk but the kind of win-win outcome the world needs.

Captured by carbon

It’s commonly understood that CO₂ is not the most potent greenhouse gas, but its huge scale of production – 2971 million tonnes (equivalent) were produced in Europe in 2024 – means that for most it’s the #1 target to go for to reduce global warming.

It’s a crucial time for Europe to take a lead as other superpowers toss out global accords. On December 10, the EU’s Council and Parliament agreed to set a legally binding climate target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90% from 1990 levels by 2040. This new target is a crucial step towards the EU’s long-term goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 – an economy with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

To this end, DAM4CO₂ is just one of eight EU research projects in the wider EIC CO2 and Nitrogen Portfolio that aims to nurture the innovations that will turn waste chemicals from agriculture, transport, health and industry into useful materials for energy.

Every journey starts with a single step, and for project manager Alessio, it wasn’t a straightforward path. “We didn’t know exactly who to contact for the conversion part at first,” he recalls. Some partnerships worked instantly; others needed rethinking. The team eventually found the right balance of expertise in catalysis, materials science, and lifecycle analysis across the seven partners in the consortium, from universities, research institutes and companies, who shared the ambition.

Behind the glass is a network of researchers stretching across the UK, Spain, Poland, and Italy, from where the project is coordinated. Many have known each other for years from doctoral programmes or earlier projects. The collaboration first sprouted from an Italian research initiative, PRIN 2020, that mandates cooperation of at least three universities or institutions – an experience that was tested when the scale of the coordinating task went from three to seven partners.

“Managing people is the hardest part. There are distinct cultures and different sensitivities. But it is precisely by bringing them together that we can create robust interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary science essential for delivering truly innovative projects.”

Heat balance: ability and capability

Technically, the team’s greatest challenge is balancing the performance to the two-sided coin that is their double-active membrane system. The membranes for capture work best in cool conditions, up to 50–60 °C, but the photocatalysis element prefers the heat, up to a sizzling 350 °C and more. “We had to find a point in the middle where both processes still work,” Alessio says. “You lose a little bit of performance on each side, but the goal is to prove that the concept works as a whole.”

And it’s the proof of concept that matters: the double-active membrane could become a new class of material arrangement for a host of sustainable chemistry applications. The potential impact is enormous. Cement manufacture, for example, is one of the world’s largest industrial sources of CO₂. In 2023, the global cement industry emitted approximately 2.4 billion metric tons of CO2, accounting for about 6% of total global emissions.

“The long-term impact is to use CO₂, waste from industries that are difficult to decarbonise, and turn it into something useful like fuels,” Alessio explains. Beyond carbon dioxide, it might one day convert toxic liquid industrial solvents into safer, reusable compounds. For now, the team’s focus is to assemble a functioning prototype, measure its limits, and decide whether to scale it up or refine the individual parts.

The human element

Having worked in France, and the Netherlands, Alessio decided to return home to Calabria in southern Italy. The DAM4CO₂ project he coordinates became a way to fulfil a personal mission to make his research, and of those around him, have a meaningful impact by helping build an innovation ecosystem where it’s most needed. “I want to help others develop ideas and innovate,” he says. “Not just basic research but creating something that society can use.”

Projects like DAM4CO₂ don’t often make headlines until the technology is proven. If the prototype works, it could inform a new generation of hybrid devices, compact and adaptable, capable of turning the problem of excess CO₂ on its head and into more of a resource. If it doesn’t, the lessons learned in materials, teamwork, metrics and design, will ripple across other fields.

“We started from an idea at Technology Readiness Level 1, almost a dream,” recalls Alessio. “Two years later, we’re holding something real in our hands. That’s what innovation feels like.”

Photo by Irene Demetri on Unsplash